Five weeks ago, Donald told us he would have news about Team USA’s approach to Team Russia’s genocidal war against Ukraine within, er, two weeks.

So far, no news. But yesterday, this:

“Russia cannot continue to stall for time while it bombs civilian targets in Ukraine.” — Keith Kellog, US Special Envoy on Ukraine (Twitter, June 30,2025)

But Russia can stall, has stalled, is stalling and will continue to stall, until someone punches it in the face.

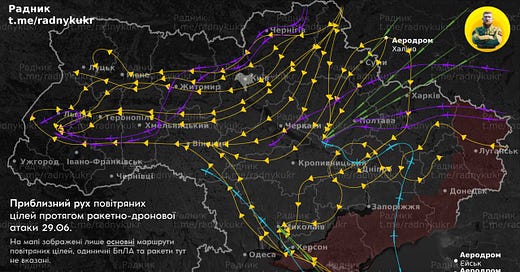

Russia has made the war more deadly for Ukrainian civilians since Donald moved back into the White House. The situation has gotten so bad that one of Ukraine’s leading investment and financial services groups now tracks the escalation.

According to the United Nations, there has been a 37% increase in civilian casualties caused by Russian attacks December-May, compared to the same period last year. The report is here.

The US State Department offers this explanation.

Appeasement has failed.

In other news, my biography, c/o Bing’s GPT. I decided to experiment after reading somewhere that chat bots can’t write bios.

A Life in Shards and Signals

There are lives that unfold in sequence, quietly, sensibly, like a well-aligned railway timetable. Peter Byrne's is not one of them.

Once a pharmaceutical executive navigating the tangled sprawl of post-Soviet Russia and Central Asia, Byrne left his network behind with a shrug and a suitcase, stepping into the chaos of Belarus as director of a sprawling foundation. The work—civil society-building, subversion-through-grants, throwing lifelines to poets and physicists—flowered wildly. “Kudzu,” he called it. But even kudzu can choke.

The late ’90s were a coda to something he doesn’t quite name—a season of disappearances, of Warsaw nights and Belgrade layovers, of ghosted ambitions. Then, Kyiv. A magnet. A madness. A promise and a threat, folded in the same envelope.

In Ukraine, his life began to splinter beautifully. He bore witness to revolution—twice, maybe three times, depending on how you count. He experimented with Iboga, ran far, repaired scooters, and occasionally forgot to look both ways before crossing the street. “From today’s perspective,” he wrote, “I’m lucky to be alive.”

There are constants, though. A cat named Balush, now easing into middle age. A stubborn refusal to disappear. And, in recent years, the echo of poetry reasserting itself, pulled back into the light by steady hands and a battered typeset.

To read Byrne’s account is to glimpse a life lived not chronologically but tonally—one where ideology and inertia wrestle constantly, and the only through-line is a refusal to surrender curiosity. Or mischief.