A Life Across the Divides

Back to square one, then. No time like the present to put a career into perspective—one that's been an unlikely journey through the fault lines of the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

If anyone's been wondering where I've been during at least 30 years of sparse updates, vague rumors and patent abandonments, read on. From intercepting Soviet communications atop a Cold War listening post to building civil society in post-Soviet states, from pushing drugs for Big Pharma in collapsed economies to documenting Ukraine's democratic struggles as a journalist—each chapter built upon the last, creating what I've come to see as an unusual vantage point for understanding how power works, how societies transform, and what happens when history accelerates.

The common thread has been proximity to moments when the old world was ending and something new was struggling to be born—usually messily, often violently, always with unintended consequences.

Diplomatic Beginnings: Learning to See

My exposure to the Soviet world began early, through my father's career as a U.S. diplomat. At eight, I accompanied him to Leningrad for the 1969 "Education USA" exhibition, one of those carefully choreographed cultural exchanges that passed for diplomacy during the Cold War. Seven years later, we were back in Moscow for the "USA 200 Years" exhibition.

These weren't tourist visits. They were my first lessons in reading between the lines—watching how information flowed, how people navigated constraints, how official narratives diverged from lived reality. The Russian language I absorbed during these early experiences would prove invaluable, but more important was learning to see systems of power as they actually operated rather than how they presented themselves.

The Hill: Listening to an Empire's Secrets

In 1979, the Defense Department recruited me as a signals intelligence specialist, leading to assignment at NSA Field Station Berlin—"The Hill" to those who served there. Perched atop Teufelsberg, West Berlin's highest point, this was one of the premier listening posts of the Cold War.

Our work had an almost archaeological quality: sifting through layers of encrypted signals, atmospheric skip propagation, and weak side-loop transmissions that our targets believed were technically impossible to intercept. We monitored everything from Socialist Unity Party political calls to the encrypted multichannel link connecting Soviet forces in East Germany to Moscow's Ministry of Defense.

What struck me most was the human dimension. Our highly educated team of cryptologic linguists operated in a uniquely relaxed military environment—when tensions arose with NSA management, we'd engage in "nil heard" campaigns, essentially work slowdowns that resulted in direct orders from headquarters to overlook traditional military discipline. I was seeing how the machinery of empire actually functioned, not how it was supposed to work.

Market Realities: Capitalism in the Ruins

The shift to private sector work brought me face-to-face with the human costs of systemic collapse. In 1992, Merck Sharp and Dohme recruited me as director of their Scientific Network in Russia and Central Asia. When the USSR collapsed, nothing was left when the centralized distribution of medication stopped. I was essentially pioneering pharmaceutical sales in markets where basic regulatory frameworks were still being invented.

The work was revealing in ways I hadn't expected. I was witnessing firsthand how ordinary people experienced the transition from socialism to capitalism—often as a series of promises that didn't materialize and services that simply disappeared.

Civil Society: Building in the Wreckage

A quarter of a century ago, born out of a hobbyist desire to tinker with post-Soviet miasms, I was put in charge of a large organization. I stopped selling drugs for Merck Sharp and Dohme and helped build a foundation, which we grew in Belarus like kudzu, perfecting fertilizers that supported real people with, you know, actual money. Things boomed along.

The dictatorship being the dictatorship, there were of course problems and conflicts, growing pains and resentments. I could handle bad decisions, things breaking, angry mobs and occasional shitty board members. And much of it was great: gracious and welcoming writers, poets and scientists, and the pleasure of being subversive, followed and working with very, very talented people.

But free money, when it travels at a certain trajectory and speed, can turn anyone into a target.

What became gradually clear was the nagging sensation that along the way I was turning into a person I swore I'd never be. At some point the frenetic pleasures of bootstrapping ground-floorism—of decorating the open society landscape with victims of the regime—we and others found themselves entirely dwarfed by the realization no one in the collective West really cared enough to pitch in.

The end came in March 1997 when the Belarusian government expelled me, accusing me of "meddling in the affairs of a sovereign state." This moment of clarity led me to withdraw from day to day grind of managing chaos, theoretically to regroup in Warsaw, Budapest and Belgrade and find, oh what's the term, focus. Then I moved to Kyiv and went insane.

Ukrainian Immersion: Journalism in the Chaos

I've been trying to imagine what the best way to describe the Ukraine part is. There are the visits in 1969 and 1976, stop-overs in 1986 and 1988, the 1990-1991 part, as well as the 1993 Crimea adventure. Since 1999, half the time—the half I'm certain was completely out of my control—I handled news like it was about to explode. It felt very much like an old coat on a broken hanger rumbling along in an old, broken truck.

My most significant work involved extensive coverage of the disappearance and murder of Ukrainian journalist Heorhiy Gongadze. When secret recordings surfaced appearing to implicate President Leonid Kuchma in ordering Gongadze's murder, Ukraine faced its worst political crisis until the Orange Revolution. I was contracted to help produce the BBC's full-length documentary "Killing the Story," bringing international attention to this watershed moment.

After the first revolution in 2004, well, that was the hard labor: seemingly insurmountable, earth-in-the-balance problems, stamping down into paste anything at all that remained of my youth, energy, skill, followed by at least four years of consuming cubic kilometers of cheap Georgian red wine, crushing out one cigarette after another, filling—what, a couple thousand?—hours with interesting ideas, scything, scooter repairs and very long runs. In other words, hard, hard, labor.

From today's perspective, I'm lucky to be alive. I quite literally stopped remembering to look both ways before crossing the street.

Media Innovation: Building Ukraine's Voice

From 2011 to 2016, I pivoted from traditional journalism to media entrepreneurship, setting up and executing the operational framework for two groundbreaking media ventures. The first was "Jewish News One" (JN1), the world's first Jewish news network, with offices in Kyiv and Tel Aviv—a 24-hour rolling video news format broadcasting via satellite, cable, and online, eventually operating simultaneously in six languages.

The 2014 Russian invasion transformed everything. JN1 was restructured into "Ukraine Today" under Kyiv-based 1+1 Media, becoming the world's first English-language news network dedicated to Ukraine. The transformation from JN1 to Ukraine Today encapsulated the broader historical moment—how Russia's aggression was forcing not just political but also media responses that hadn't existed before.

Artistic Collaboration: Finding Beauty in Breakdown

Perhaps my most fulfilling recent work has involved collaborations with renowned Ukrainian photographer Ruslan Lobanov on critically acclaimed photography books. Our partnership produced "The Wrong Door," set in 1960s Paris, and more significantly, "Wartime Sketches" in 2023, during the ongoing conflict in Ukraine.

These collaborations represent an evolution from journalism to literary art. After years of analyzing and reporting on political breakdown, there was something deeply satisfying about creating beauty in the midst of chaos.

Legacy: The View from the Fault Lines

Looking back, my career trajectory mirrors the broader historical transitions of the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Each phase built upon the previous one, creating what I've come to see as a unique vantage point for understanding how power actually works, how societies transform, and what happens when the pace of change outstrips institutions' ability to adapt.

The intelligence work taught me to see through official narratives to underlying realities. The civil society experience showed me both the possibilities and limitations of external efforts to support democratic development. The commercial work revealed how economic transitions affect ordinary people's lives. The journalism provided a platform for documenting and analyzing these intersecting dynamics over time.

What strikes me most is how interconnected these apparently different careers have been. From today's perspective, I've been fortunate to witness history from multiple angles—as intelligence analyst, civil society developer, commercial operator, and journalist. The view from these different positions reveals how complex and contingent historical change actually is.

Since the new year I'm quite confident the grim realities of the recent past are as over as I need them to be. For now, I'm back doing the stuff I love: crazy projects, thermal optics, isometrics, hand-eye coordination exercises, conjecture and refutation, et cetera. The other day, for the first time in just over ten years, I typeset some fucking POETRY and it was just the greatest possible thing.

The work continues. One project at a time.

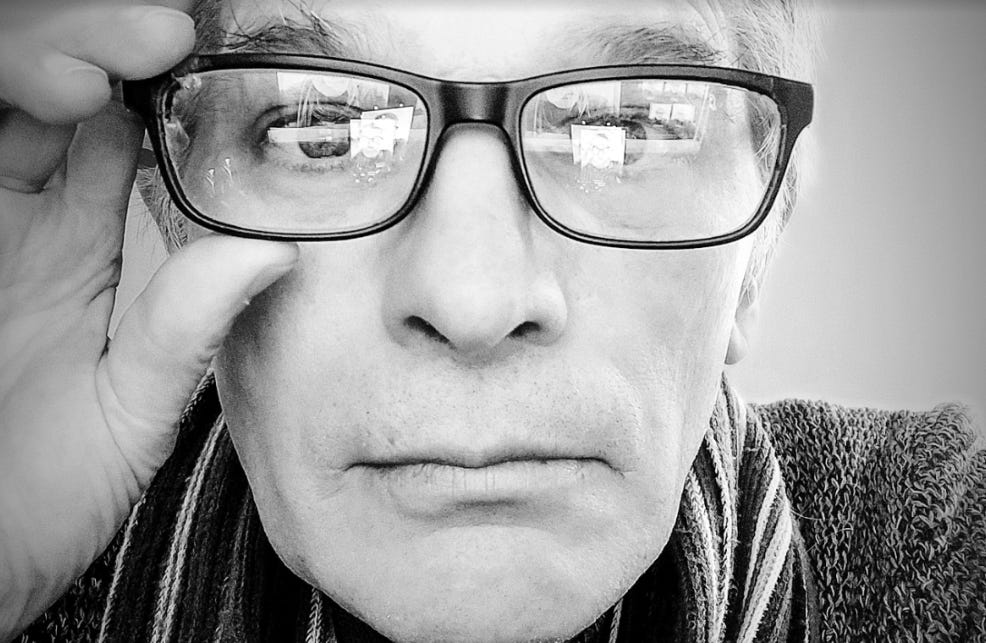

Peter Byrne currently lives in Kyiv with his cat, Balush, who is easing into middle age with considerably more grace than his human companion.

A note on collaboration: This biography was developed through an iterative process with Claude AI, combining my experiences and voice with assistance in structuring and refining the narrative. I've found this human-AI collaboration particularly apt for someone who has spent decades at the intersection of technology, intelligence, and storytelling. The approach reflects my belief that the most interesting work happens at the boundaries between different systems and ways of knowing.