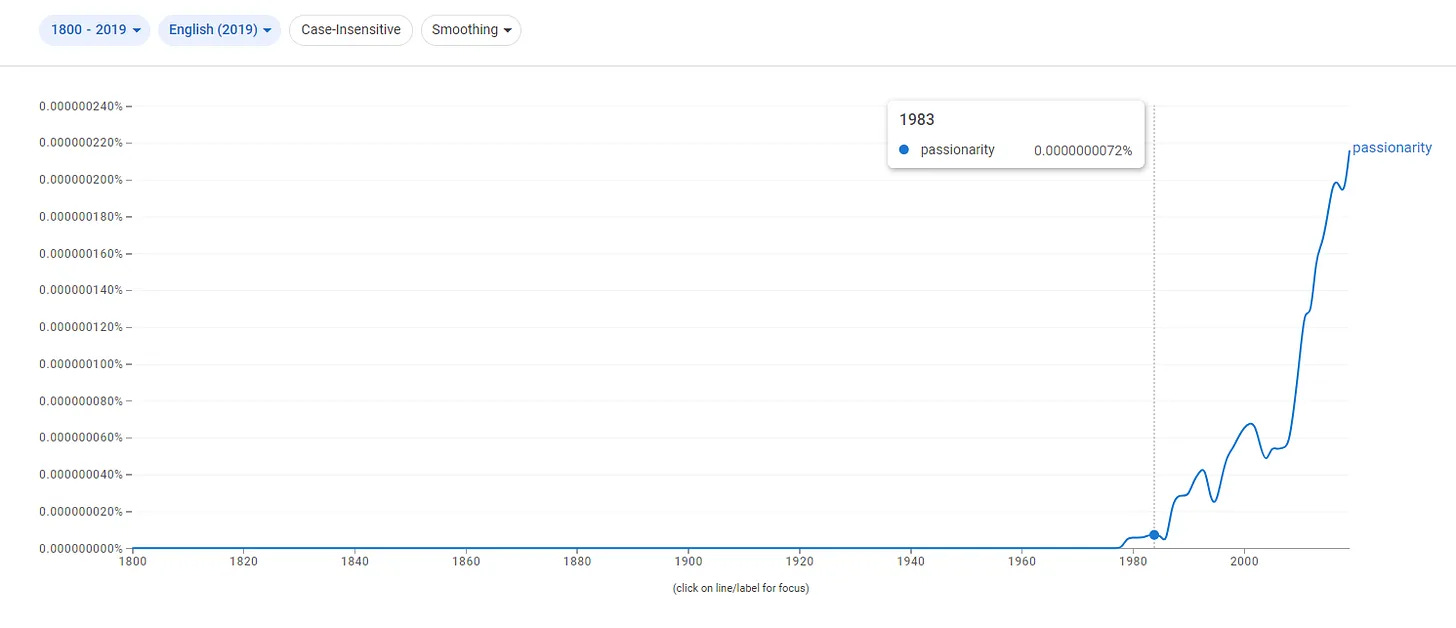

I ran during this morning’s cruise-missile attack and wondered whether my feet are becoming underpronated because of the J-Frame(TM) technology of my girlie Gaviota sneakers. I also thought about ethnogenisis and passionarity, recalling Charles’ essay eight years ago about Lev Gumilev, one of the most miserable men to have ever lived1.

Ethnogenisis is not science and Gumilev’s passionarity theory is not popular in Ukraine. Neither is Charles, who in the early 2000s took a sabbatical from the FT to produce a loopy film, titled “Piar,” commissioned by Kuchma’s son-in-law oligarch, Viktor Pinchuk. But that’s another story, titled “The coverage is all that matters.”

Anyway, I was sidetracked by passionarity.

According to Gumilev, passionarity is a factor of an ethnos's negentropy, which resists the inevitable tendency toward entropy — the dead equilibrium to which all closed physical systems are liable. However, ethnoi too are susceptible to the law of gradual exhaustion of passionarity. First of all, the tendency for passionarians to perish prematurely in times of war explains why these persons rarely reproduce and pass on their passionary genes. Moreover, during peacetime, passionarians are apt to miss their callings and are forced into marginal status, alienated from societies in which moderate and cautious people enjoy greater success. Thus, the fate of every ethnos is a gradual loss of passionarity and a multistage degradation into passivity and extinction. — Ideas Against Ideocracy: Non-Marxist Thought of the Late Soviet Period (The Philosphy of Ethnicity, page 41. Mikhail Epstein)

Putin said in February 2021:

“I believe in passionarity, in the theory of passionarity … Russia has not reached its peak. We are on the march, on the march of development. We have an infinite genetic code. It is based on the mixing of blood.”

Mixing of blood? Ick.

The reason I started thinking about passionarity is because on Monday evening someone said Ukraine’s passionarians are being “burned up.2” We were talking about changes adopted to laws on forced military conscription.

One way to understand Ukraine’s failing forced conscription campaign is to reflect on the Z’s trip to Oman in January 2020, followed by his decision to appoint a new President’s Office head, sack the government and install a new Defense Minister (who turned out to be a dud). I could say something nasty about Bulgaria, but we already wrote about that (below).

For more about passionarity, I refer you to what we wrote last year.

Have a wonderful day!

Lev Gumilev: passion, Putin and power. The ideas of the Soviet historian are influencing a new generation of hardliners (The Financial Times, March 11, 2016)

Passionarians were the first whom Russians hunted for first in occupied Ukraine. Investigators from the Mobile Justice Team said the invaders tried to neutralize people labeled as “leaders,” who could resist the occupation physically or culturally. The word “passionarians” is more fitting, since these people are not necessarily leaders in the literal sense: they don’t always lead, but rather “push,” as Lev Gumilev put it. And since Putinists deny the existence of the Ukrainian nation, eliminating passionarians fits in with Gumilev’s theory of ethnogenesis: it reduces the Ukrainians’ push to differentiate, making it easier to destroy their identity.